16th Oct, 2021 10:00

TWO-DAY AUCTION - Fine Chinese Art / 中國藝術集珍 / Buddhism & Hinduism

366

A RARE AND MONUMENTAL PAINTED MARBLE FIGURE OF A ‘WINE SERVANT’, LIAO DYNASTY

遼代罕見的大型彩繪大理石侍酒師像

Sold for €15,168

including Buyer's Premium

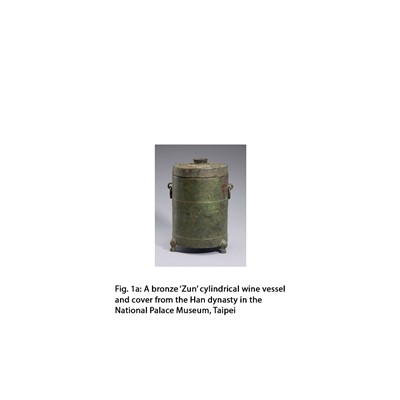

China, Liao (916-1125) or Jin (1115-1234). Superbly carved and skillfully painted in polychrome pigments, this ancient ‘Sommelier’ presents a cylindrical wine vessel ‘Zun’ (see fig. 1a) held with both hands in front of him, hidden under the elongated sleeves of his robe. The protruding lid and the distinct knob of the Zun, however, are well visible.

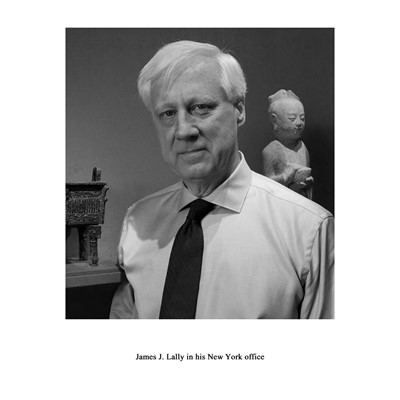

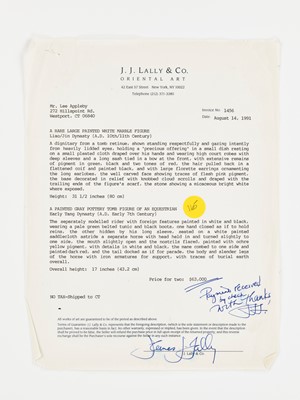

Provenance: J.J. Lally & Co., New York, 14 August 1991. Estates of William R. Appleby (1915-2007) and Elinor Appleby (1920-2020), acquired from the above. The original invoice no. 1456 from J.J. Lally & Co., signed by James J. Lally, dated 14 August 1991, stating a purchase price of USD 63,000 (approximately USD 122,500 in today’s currency) for the present lot and a smaller item accompanies this lot. It dates the figure to the 10th-11th century and describes it as a “dignitary […] holding a precious offering”. William and Elinor Appleby were noted New York Asian art collectors and longtime donors to the Asian Department at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

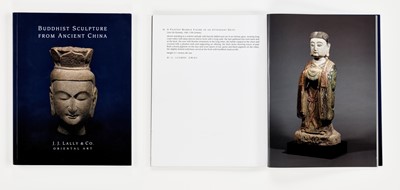

Published: J. J. Lally & Co. Oriental Art, New York, Buddhist Sculpture from Ancient China, March 2017, number 18. The statue was loaned by Elinor Appleby (1920-2020) to J. J. Lally & Co for this special exhibition.

Condition: Excellent condition, fully commensurate with age, extensive wear to the stone and pigments, small nicks and losses, weathering and erosion, minor structural cracks. Overall exactly as expected of a statue that was created over a millennium ago. The pigments have darkened significantly over the centuries. The marble has a fine, unctuous patina that has naturally grown into an elegant, creamy tone over time.

Weight: 65.9 kg (incl. base)

Dimensions: Height 77 cm (excl. base) and 85 cm (incl. base)

With a fitted wood base. (2)

The wine servant is adorned in floral earrings, his hair neatly pulled back, the face showing a meditative yet somewhat hedonist expression, with heavy-lidded eyes below gently arched eyebrows, a prominent nose, and full lips slightly pursed to form a subtle smile. He stands on a rectangular base incised with cloud scrolls to the front, and wears a long flowing robe elegantly tied with a sash and a scarf neatly falling over the base.

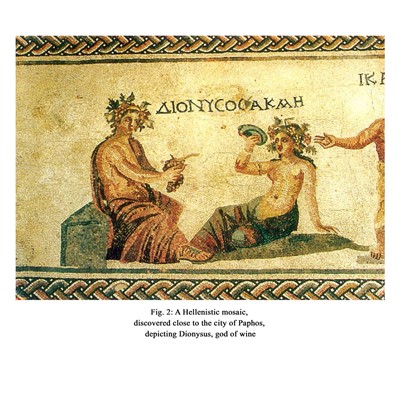

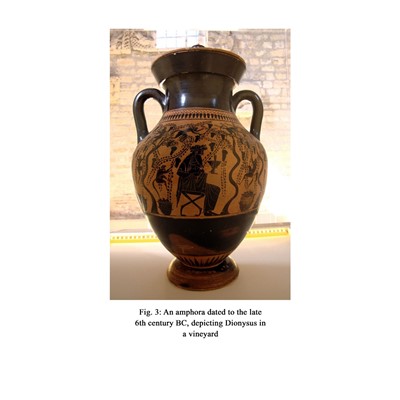

The ancient Greeks were highly influential in the development and distribution of wine and the emergence of their winemaking culture was symbolized by the mythology of Dionysus, god of wine (see fig. 2). Greek wine became widely appreciated and was exported throughout the Mediterranean, the Levante and even further into the east, as wine amphoras with distinct Greek styling and art have been found throughout these areas (see fig. 3).

The Hellenization of Central Asia, through the military conquests of Alexander (see fig. 4), eventually brought viticulture and winemaking further eastward. In response to his disastrous journey through the Gedrosia desert, located in today’s Iran, Pakistan and India, in which perhaps one-third of his troops lost their lives, Alexander staged a Bacchic triumphal procession and celebrated a drinking party in honor of Dionysus that lasted seven days and seven nights. In the territory of the ancient Gandhara Kingdom, the Macedonian army was even believed to have discovered the birthplace of Dionysus, because the mountainous landscape was so rich in wild grapes. In the region, wine was indeed consumed during popular religious festivals already long before the arrival of Buddhism.

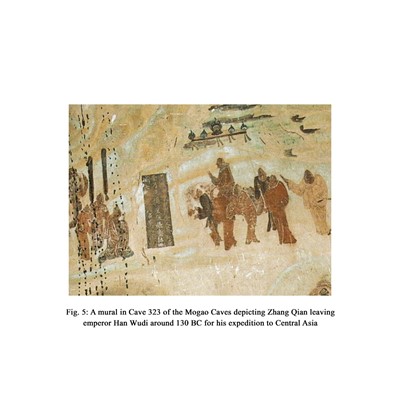

In the 130s and 120s BC, a Chinese imperial envoy of the Han dynasty named Zhang Qian (see fig. 5) opened diplomatic relations with several Hellenistic successor states in Central Asia, including Dayuan, Sogdia, and Bactria. By the end of the second century BC, Han envoys had brought grape seeds from the wine-loving kingdom of Dayuan in the Fergana Valley back to China and had them planted on Imperial land near the capital Chang'an. The Shennong Ben Cao Jing, the oldest surviving Chinese work on materia medica, compiled in the late Han, states that grapes could be used to produce wine. In the Three Kingdoms era, Wei Emperor Cao Pi (d. 226 AD) noted that grape wine “is sweeter than the wine made [from cereals] using ferments and sprouted grain. One recovers from it more easily when one has taken too much.” Grapes continued to be grown in the following centuries, notably in the northwestern region of Gansu, but were not yet used to produce wine on a large scale. Wine thus remained an exotic product known to only very few people.

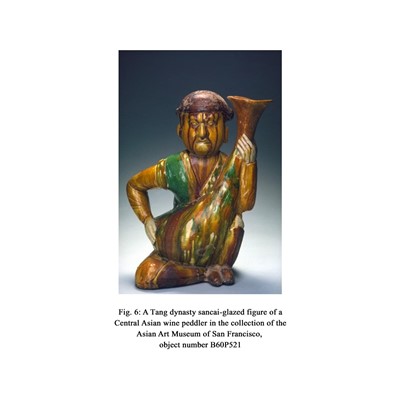

During the Tang dynasty, the consumption of grape wines became more common. With the conquest of the silk road state Gaochang in 641, the Tang obtained the seeds of an elongated grape called ‘mare teat’ (maru) as well as a method for winemaking. Later, wine was also imported again following the restoration of trade with the west, as evidenced by tomb figures depicting Central Asian wine merchants (see fig. 6).

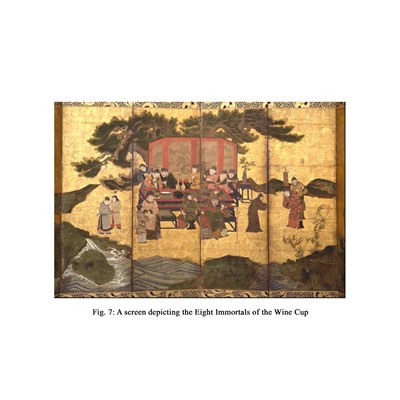

Several Tang poets versified on grape wine, celebrating wine from the ‘Western Regions’ – the one from Liangzhou was particularly noted – or from Taiyuan in Shanxi, the latter of which produced wine made from the ‘mare teat’ grape. Emperor Muzong of Tang (795-824), who spent much of his brief reign feasting and heavily drinking, said of this wine: “When I drink this, I am instantly conscious of harmony suffusing my four limbs. It is the true Princeling of Grand Tranquility!” The Eight Immortals of the Wine Cup (see fig. 7) were a group of Tang dynasty scholars that included the great Li Bai (701-762). These accomplished and influential poets were known for their love of wine, a fact that is supported by their many writings related to it.

Expert’s note: The growing popularity of wine in China, beginning in the Tang dynasty, is attested by the great Tang poets as well as tomb figures of Central Asian wine merchants, highlighting aspects of refined taste and artistic intoxication on the one hand, and the importance of trade and globalization to Tang society, epitomized by the Silk Road, on the other. The present figure, of massive size yet fine quality, most likely served as a tomb attendant for a person of high status who would have looked forward to drinking much wine in the afterlife, while “recovering from it more easily when one has taken too much.”

Literature comparison: The heaviness of the face and square jawline seen on the present figure are characteristic of sculpture dating to the late Tang (AD 618-907) to Liao dynasty (AD 916-1125). See, for example, a marble seated figure of Buddha dated to the late Tang dynasty in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, where the fullness of the face is particularly prominent, illustrated by Denise Patry Leidy and Donna Strahan in Wisdom Embodied: Chinese Buddhist and Daoist Sculpture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New Haven, 2010, p. 176, no. A28.

Literature: A bronze wine vessel and cover dated to the Han dynasty, of similar cylindrical form with a short circular knob surmounting the cover, is in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei, see figs. 1a and 1b. See also fig. 2, a Hellenistic mosaic, discovered close to the city of Paphos, depicting Dionysus. See fig. 3, an amphora dated to the late 6th century BC, depicting Dionysus in a vineyard. See fig. 4, a mosaic from Pompeii depicting Alexander the Great. See fig. 5, a mural in Cave 323 of the Mogao Caves depicting Zhang Qian leaving emperor Han Wudi around 130 BC for his expedition to Central Asia. See fig. 6, a Tang-dynasty sancai-glazed figure of a Central Asian wine peddler in the collection of the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, object number B60P521. See fig. 7, a screen depicting the Eight Immortals of the Wine Cup.

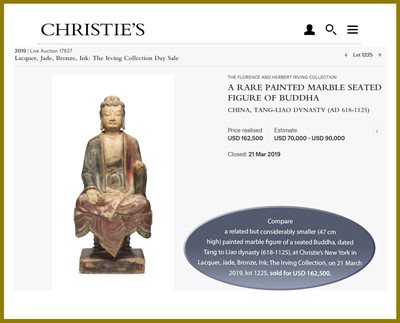

Auction result comparison: Compare a related but considerably smaller (47 cm high) painted marble figure of a seated Buddha, dated Tang to Liao dynasty (618-1125), at Christie’s New York in Lacquer, Jade, Bronze, Ink: The Irving Collection, on 21 March 2019, lot 1225, sold for USD 162,500.

遼代罕見的大型彩繪大理石侍酒師像

中國,遼代 (916-1125) 或金代 (1115-1234),這位古時的侍酒師雕刻精美,彩繪生動。他雙手置於胸前持一個酒器(見圖 1a),藏在長袍的長袖下。 不過,仍可看出酒器的蓋子和蓋鈕。

來源:紐約J.J. Lally & Co.藝廊,1991年8月14 日。William R. Appleby (1915-2007) 與 Elinor Appleby (1920-2020)收藏,購於上述藝廊。隨附J.J. Lally & Co.的原始發票(票號 1456),James J. Lally簽名,日期為1991年8月14日,價格為 USD 63,000 (相當於如今的USD 122,500),包括該拍品已經另一件小物品。時間推斷為十至十一世紀,並描述爲 “dignitary […] holding a precious offering”(手持祭祀用品)。William 與 Elinor Appleby 夫婦曾是紐約知名亞洲藝術收藏家,長期資助紐約大都會博物館亞洲部。

出版:在紐約J. J. Lally & Co. Oriental Art藝廊 出版的“ Buddhist Sculpture from Ancient China”,2017年3月,18號。Elinor Appleby (1920-2020) 因爲這個特殊的展覽出借造像給 J. J. Lally & Co。

品相:狀況極佳,與年齡完全相稱,石材和顏料大面積磨損,可見小刻痕和缺損、風化和侵蝕,輕微的結構性裂縫。 總體而言,完全符合一千年前造像的預期。 幾個世紀以來,顏料明顯變暗。 大理石造像表面具有細膩的光澤。

重量:65.9 公斤 (含底座)

尺寸:高 77 厘米 (不含底座),85 厘米 (含底座)

配套木底座 (2)

專家注釋:從唐代開始,葡萄酒在中國開始普及,唐代詩詞以及中亞出土的墓葬人物都可以證明,一方面是因爲突出了高雅的品味和藝術性以及貿易的重要性;另一方面,絲綢之路體現唐時社會的全球化。 造像身形龐大,質量上乘,很有可能是有地位的人的守墓人,希望在另一世界也能夠多飲美酒。

拍賣結果比較:一件相近但小很多 (高47 厘米) 的彩繪大理石坐佛,唐至遼代 (618-1125), 見紐約佳士得 Lacquer, Jade, Bronze, Ink: The Irving Collection2019年3月21日 lot 1225, 售價USD 162,500。

China, Liao (916-1125) or Jin (1115-1234). Superbly carved and skillfully painted in polychrome pigments, this ancient ‘Sommelier’ presents a cylindrical wine vessel ‘Zun’ (see fig. 1a) held with both hands in front of him, hidden under the elongated sleeves of his robe. The protruding lid and the distinct knob of the Zun, however, are well visible.

Provenance: J.J. Lally & Co., New York, 14 August 1991. Estates of William R. Appleby (1915-2007) and Elinor Appleby (1920-2020), acquired from the above. The original invoice no. 1456 from J.J. Lally & Co., signed by James J. Lally, dated 14 August 1991, stating a purchase price of USD 63,000 (approximately USD 122,500 in today’s currency) for the present lot and a smaller item accompanies this lot. It dates the figure to the 10th-11th century and describes it as a “dignitary […] holding a precious offering”. William and Elinor Appleby were noted New York Asian art collectors and longtime donors to the Asian Department at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Published: J. J. Lally & Co. Oriental Art, New York, Buddhist Sculpture from Ancient China, March 2017, number 18. The statue was loaned by Elinor Appleby (1920-2020) to J. J. Lally & Co for this special exhibition.

Condition: Excellent condition, fully commensurate with age, extensive wear to the stone and pigments, small nicks and losses, weathering and erosion, minor structural cracks. Overall exactly as expected of a statue that was created over a millennium ago. The pigments have darkened significantly over the centuries. The marble has a fine, unctuous patina that has naturally grown into an elegant, creamy tone over time.

Weight: 65.9 kg (incl. base)

Dimensions: Height 77 cm (excl. base) and 85 cm (incl. base)

With a fitted wood base. (2)

The wine servant is adorned in floral earrings, his hair neatly pulled back, the face showing a meditative yet somewhat hedonist expression, with heavy-lidded eyes below gently arched eyebrows, a prominent nose, and full lips slightly pursed to form a subtle smile. He stands on a rectangular base incised with cloud scrolls to the front, and wears a long flowing robe elegantly tied with a sash and a scarf neatly falling over the base.

The ancient Greeks were highly influential in the development and distribution of wine and the emergence of their winemaking culture was symbolized by the mythology of Dionysus, god of wine (see fig. 2). Greek wine became widely appreciated and was exported throughout the Mediterranean, the Levante and even further into the east, as wine amphoras with distinct Greek styling and art have been found throughout these areas (see fig. 3).

The Hellenization of Central Asia, through the military conquests of Alexander (see fig. 4), eventually brought viticulture and winemaking further eastward. In response to his disastrous journey through the Gedrosia desert, located in today’s Iran, Pakistan and India, in which perhaps one-third of his troops lost their lives, Alexander staged a Bacchic triumphal procession and celebrated a drinking party in honor of Dionysus that lasted seven days and seven nights. In the territory of the ancient Gandhara Kingdom, the Macedonian army was even believed to have discovered the birthplace of Dionysus, because the mountainous landscape was so rich in wild grapes. In the region, wine was indeed consumed during popular religious festivals already long before the arrival of Buddhism.

In the 130s and 120s BC, a Chinese imperial envoy of the Han dynasty named Zhang Qian (see fig. 5) opened diplomatic relations with several Hellenistic successor states in Central Asia, including Dayuan, Sogdia, and Bactria. By the end of the second century BC, Han envoys had brought grape seeds from the wine-loving kingdom of Dayuan in the Fergana Valley back to China and had them planted on Imperial land near the capital Chang'an. The Shennong Ben Cao Jing, the oldest surviving Chinese work on materia medica, compiled in the late Han, states that grapes could be used to produce wine. In the Three Kingdoms era, Wei Emperor Cao Pi (d. 226 AD) noted that grape wine “is sweeter than the wine made [from cereals] using ferments and sprouted grain. One recovers from it more easily when one has taken too much.” Grapes continued to be grown in the following centuries, notably in the northwestern region of Gansu, but were not yet used to produce wine on a large scale. Wine thus remained an exotic product known to only very few people.

During the Tang dynasty, the consumption of grape wines became more common. With the conquest of the silk road state Gaochang in 641, the Tang obtained the seeds of an elongated grape called ‘mare teat’ (maru) as well as a method for winemaking. Later, wine was also imported again following the restoration of trade with the west, as evidenced by tomb figures depicting Central Asian wine merchants (see fig. 6).

Several Tang poets versified on grape wine, celebrating wine from the ‘Western Regions’ – the one from Liangzhou was particularly noted – or from Taiyuan in Shanxi, the latter of which produced wine made from the ‘mare teat’ grape. Emperor Muzong of Tang (795-824), who spent much of his brief reign feasting and heavily drinking, said of this wine: “When I drink this, I am instantly conscious of harmony suffusing my four limbs. It is the true Princeling of Grand Tranquility!” The Eight Immortals of the Wine Cup (see fig. 7) were a group of Tang dynasty scholars that included the great Li Bai (701-762). These accomplished and influential poets were known for their love of wine, a fact that is supported by their many writings related to it.

Expert’s note: The growing popularity of wine in China, beginning in the Tang dynasty, is attested by the great Tang poets as well as tomb figures of Central Asian wine merchants, highlighting aspects of refined taste and artistic intoxication on the one hand, and the importance of trade and globalization to Tang society, epitomized by the Silk Road, on the other. The present figure, of massive size yet fine quality, most likely served as a tomb attendant for a person of high status who would have looked forward to drinking much wine in the afterlife, while “recovering from it more easily when one has taken too much.”

Literature comparison: The heaviness of the face and square jawline seen on the present figure are characteristic of sculpture dating to the late Tang (AD 618-907) to Liao dynasty (AD 916-1125). See, for example, a marble seated figure of Buddha dated to the late Tang dynasty in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, where the fullness of the face is particularly prominent, illustrated by Denise Patry Leidy and Donna Strahan in Wisdom Embodied: Chinese Buddhist and Daoist Sculpture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New Haven, 2010, p. 176, no. A28.

Literature: A bronze wine vessel and cover dated to the Han dynasty, of similar cylindrical form with a short circular knob surmounting the cover, is in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei, see figs. 1a and 1b. See also fig. 2, a Hellenistic mosaic, discovered close to the city of Paphos, depicting Dionysus. See fig. 3, an amphora dated to the late 6th century BC, depicting Dionysus in a vineyard. See fig. 4, a mosaic from Pompeii depicting Alexander the Great. See fig. 5, a mural in Cave 323 of the Mogao Caves depicting Zhang Qian leaving emperor Han Wudi around 130 BC for his expedition to Central Asia. See fig. 6, a Tang-dynasty sancai-glazed figure of a Central Asian wine peddler in the collection of the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, object number B60P521. See fig. 7, a screen depicting the Eight Immortals of the Wine Cup.

Auction result comparison: Compare a related but considerably smaller (47 cm high) painted marble figure of a seated Buddha, dated Tang to Liao dynasty (618-1125), at Christie’s New York in Lacquer, Jade, Bronze, Ink: The Irving Collection, on 21 March 2019, lot 1225, sold for USD 162,500.

遼代罕見的大型彩繪大理石侍酒師像

中國,遼代 (916-1125) 或金代 (1115-1234),這位古時的侍酒師雕刻精美,彩繪生動。他雙手置於胸前持一個酒器(見圖 1a),藏在長袍的長袖下。 不過,仍可看出酒器的蓋子和蓋鈕。

來源:紐約J.J. Lally & Co.藝廊,1991年8月14 日。William R. Appleby (1915-2007) 與 Elinor Appleby (1920-2020)收藏,購於上述藝廊。隨附J.J. Lally & Co.的原始發票(票號 1456),James J. Lally簽名,日期為1991年8月14日,價格為 USD 63,000 (相當於如今的USD 122,500),包括該拍品已經另一件小物品。時間推斷為十至十一世紀,並描述爲 “dignitary […] holding a precious offering”(手持祭祀用品)。William 與 Elinor Appleby 夫婦曾是紐約知名亞洲藝術收藏家,長期資助紐約大都會博物館亞洲部。

出版:在紐約J. J. Lally & Co. Oriental Art藝廊 出版的“ Buddhist Sculpture from Ancient China”,2017年3月,18號。Elinor Appleby (1920-2020) 因爲這個特殊的展覽出借造像給 J. J. Lally & Co。

品相:狀況極佳,與年齡完全相稱,石材和顏料大面積磨損,可見小刻痕和缺損、風化和侵蝕,輕微的結構性裂縫。 總體而言,完全符合一千年前造像的預期。 幾個世紀以來,顏料明顯變暗。 大理石造像表面具有細膩的光澤。

重量:65.9 公斤 (含底座)

尺寸:高 77 厘米 (不含底座),85 厘米 (含底座)

配套木底座 (2)

專家注釋:從唐代開始,葡萄酒在中國開始普及,唐代詩詞以及中亞出土的墓葬人物都可以證明,一方面是因爲突出了高雅的品味和藝術性以及貿易的重要性;另一方面,絲綢之路體現唐時社會的全球化。 造像身形龐大,質量上乘,很有可能是有地位的人的守墓人,希望在另一世界也能夠多飲美酒。

拍賣結果比較:一件相近但小很多 (高47 厘米) 的彩繪大理石坐佛,唐至遼代 (618-1125), 見紐約佳士得 Lacquer, Jade, Bronze, Ink: The Irving Collection2019年3月21日 lot 1225, 售價USD 162,500。

Zacke Live Online Bidding

Our online bidding platform makes it easier than ever to bid in our auctions! When you bid through our website, you can take advantage of our premium buyer's terms without incurring any additional online bidding surcharges.

To bid live online, you'll need to create an online account. Once your account is created and your identity is verified, you can register to bid in an auction up to 12 hours before the auction begins.

Intended Spend and Bid Limits

When you register to bid in an online auction, you will need to share your intended maximum spending budget for the auction. We will then review your intended spend and set a bid limit for you. Once you have pre-registered for a live online auction, you can see your intended spend and bid limit by going to 'Account Settings' and clicking on 'Live Bidding Registrations'.

Your bid limit will be the maximum amount you can bid during the auction. Your bid limit is for the hammer price and is not affected by the buyer’s premium and VAT. For example, if you have a bid limit of €1,000 and place two winning bids for €300 and €200, then you will only be able to bid €500 for the rest of the auction. If you try to place a bid that is higher than €500, you will not be able to do so.

Online Absentee and Telephone Bids

You can now leave absentee and telephone bids on our website!

Absentee Bidding

Once you've created an account and your identity is verified, you can leave your absentee bid directly on the lot page. We will contact you when your bids have been confirmed.

Telephone Bidding

Once you've created an account and your identity is verified, you can leave telephone bids online. We will contact you when your bids have been confirmed.

Classic Absentee and Telephone Bidding Form

You can still submit absentee and telephone bids by email or fax if you prefer. Simply fill out the Absentee Bidding/Telephone bidding form and return it to us by email at office@zacke.at or by fax at +43 (1) 532 04 52 20. You can download the PDF from our Upcoming Auctions page.

How-To Guides

How to Create Your Personal Zacke Account

How to Register to Bid on Zacke Live

How to Leave Absentee Bids Online

How to Leave Telephone Bids Online

中文版本的操作指南

创建新账号

注册Zacke Live在线直播竞拍(免平台费)

缺席投标和电话投标

Third-Party Bidding

We partner with best-in-class third-party partners to make it easy for you to bid online in the channel of your choice. Please note that if you bid with one of our third-party online partners, then there will be a live bidding surcharge on top of your final purchase price. You can find all of our fees here. Here's a full list of our third-party partners:

- 51 Bid Live

- EpaiLive

- ArtFoxLive

- Invaluable

- LiveAuctioneers

- the-saleroom

- lot-tissimo

- Drouot

Please note that we place different auctions on different platforms. For example, in general, we only place Chinese art auctions on 51 Bid Live.

Bidding in Person

You must register to bid in person and will be assigned a paddle at the auction. Please contact us at office@zacke.at or +43 (1) 532 04 52 for the latest local health and safety guidelines.