5th Mar, 2021 10:00

TWO-DAY AUCTION - Fine Chinese Art / 中國藝術集珍 / Buddhism & Hinduism

234

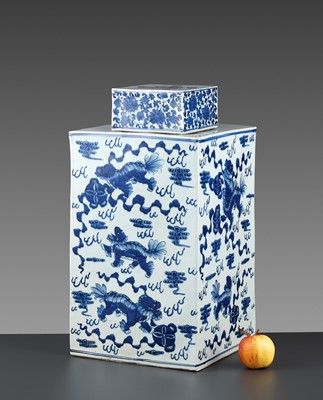

A LARGE AND MASSIVE ‘DOUBLE VAJRA’ PORCELAIN CADDY FOR SACRED TEA, LATE MING

明代末期大型青花金剛杵茶葉罐

Sold for €3,539

including Buyer's Premium

China, late 15th to mid-17th century. Of square form, the sides painted with Buddhist lions and cubs with brocade balls and ribbons surrounded by scrolling clouds and flames, the cover with a continuous lotus scroll to the sides and a visvavajra, the utter symbol of protection, at the top. The interior is fortified with a vertical flange to each side, supporting the considerable weight of this storage canister.

Provenance: British private collection.

Condition: Overall in good condition with wear, firing flaws, kiln grit, pitting, and fritting, the unglazed ware burnt to orange at the base, all exactly as expected on late Ming wares. Small hairlines, traces of usage and minor losses around the foot rim. Two areas of old repair to shallow surface chips (ca. 3 x 3 cm each).

Weight: 16.4 kg (excl. cover) and 1,576 g (the cover)

Dimensions: Height 50.4 cm

The present caddy was used to store ‘Dian’ tea, served only in a sacred hall where all the monks of a monastery or temple would gather before the Buddha, after the tea bell was struck by the tea monk as an initiation of the tea ceremony.

The visvavajra on the cover is a most potent and indestructible symbol of protection, placed in this particular spot not only to dispel evil, temptation, and deception from the four directions, but also to repudiate individuals from withdrawing - thus desecrating - the precious contents of this caddy.

The double vajra motif appears to have entered the Chinese repertoire of porcelain designs with the increased popularity of Lamaism – Tibetan Buddhism - in the Yuan dynasty. As early as 1207 Ghengis Khan sent envoys to Tibet, and a system developed so that Tibet accepted Mongol protection and suzerainty while providing the Mongols with spiritual guidance. In 1239, however, a Mongol army under Koden, second son of Ogodai Khan attacked Tibet, and the Tibetans decided to negotiate. The result was that Tibet submitted to the Mongols and the latter appointed the abbot of the Sakya monastery to exercise political authority over the whole of Tibet. The magic of Tantric Buddhism appealed to the Mongols and when they were initiated into the practices of Lamaism, they began to adopt that type of Buddhism to take the place of their own Shamanism.

When Kublai Khan took over the great Khanate in 1260, he made Lamaism the national religion of the Mongols. After the Mongols established the Yuan dynasty in China in 1279, Lamaism flourished, receiving huge grants of land from the ruling house and the nobility. Tibetan Buddhist iconography appeared on objects in a variety of media made for the Yuan court. These included motifs such as the double vajra, which is seen on blue and white porcelain of the period. The influence of Lamaism on these porcelains came not only from the interests of the Mongols themselves, but from the Tibetan and Nepalese craftsmen who held high positions at the imperial porcelain kiln at Jingdezhen. The famous Nepalese artist Aniko (1245-1306) was appointed head of the Imperial workshops in 1278.

In the Ming dynasty a number of the Chinese emperors had a genuine interest in Lamaist Buddhism, but they also patronized Lamaism as a way of maintaining control over both the Tibetans and the Mongols, through the support of the powerful high lamas. The Yongle Emperor involved both Tibetan and Nepalese craftsmen in the building of his new palace in Beijing. He also involved them in the running of the Imperial workshops, as had the previous Mongol dynasty. Their influence can clearly be seen in the works such as exquisite gilt-bronze Buddhist figures in Tibetan-Chinese style made during this reign. These pieces and those of the succeeding Xuande period (1426-35) were made with reign marks and for ritual use by the Imperial household or as gifts from the emperor to high Tibetan lamas favored by the Chinese court.

During the reign of the Chenghua Emperor (1465-87) there were 437 Tibetan monks holding high rank and 789 lamas who could enter the court freely. The emperor’s advisers became concerned by this preoccupation with Buddhism and the amount spent by the emperor in connection with it, so that they suggested a sharp reduction in his support of Buddhism. This appears to have been adopted for the middle part of his reign, but his resumption of expressed interest in Buddhism can clearly be observed through the arts produced in the latter years of the Chenghua reign. Among these, the ceramics made at the imperial kiln provide a good indication of the incorporation of Buddhist motifs, including Tibetan Buddhist motifs, on porcelains made for the court.

Literature comparison: A somewhat simpler double-vajra and ribbon design can be seen on the interior of a blue and white dish, in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing, illustrated in Blue and White Porcelain with Underglaze Red (II), The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum, vol. 35, Hong Kong, 2000, p. 9, no. 7. A dish with double vajra on the interior, which is similar to the Beijing dish, was excavated at the Ming imperial kilns from the late Chenghua stratum and is illustrated in The Emperor’s broken china – Reconstructing Chenghua porcelain, London, 1995, p. 77, no. 102. A double vajra can also be seen in the central medallion on the interior of a large blue and white bowl in the collection of the Idemitsu Museum, illustrated in Chinese Ceramics in the Idemitsu Collection, Tokyo, 1987, color plate 140. Compare also to a dish with a double vajra from the collection of Sir John Addis, illustrated by Jessica Harrison-Hall in Ming Ceramics in the British Museum, London, 2001, no. 6:10.

Auction result comparison: Compare with a blue and white dish from the Ming dynasty, showing a closely related double vajra as on the present caddy, at Christie’s London in Rarity and Refinement: Treasures from a Distinguished East Asian Collection, on 15 May 2018, lot 7, sold for GBP 81,250.

明代末期大型青花金剛杵茶葉罐

中國,十五世紀末至十七世紀中葉。茶葉罐外壁可見太獅少獅戲珠圖,四周是滾動的雲彩和火焰,頂部纏枝蓮紋,側面可見金剛杵。

來源:英國私人收藏.

品相:總體而言狀況良好,有磨損,燒傷缺陷,窯渣,麻點和燒結現象,露胎部部成橙色,完全符合明代晚期瓷器的特徵。 細小的裂縫,使用痕跡和腳沿周圍的輕微磕損。有兩處舊時修復區域小開片(每片約3 x 3厘米)。

重量:不含蓋16.4 公斤;蓋1,576 克

尺寸:高50.4厘米

拍賣結果比較:於2018年5月15日 倫敦佳士得 Rarity and Refinement: Treasures from a Distinguished East Asian Collection 拍場中,與一件明代時期藍白盤比較,出与本罐密切相关的双金刚,lot 7,售價GBP 81,250。

China, late 15th to mid-17th century. Of square form, the sides painted with Buddhist lions and cubs with brocade balls and ribbons surrounded by scrolling clouds and flames, the cover with a continuous lotus scroll to the sides and a visvavajra, the utter symbol of protection, at the top. The interior is fortified with a vertical flange to each side, supporting the considerable weight of this storage canister.

Provenance: British private collection.

Condition: Overall in good condition with wear, firing flaws, kiln grit, pitting, and fritting, the unglazed ware burnt to orange at the base, all exactly as expected on late Ming wares. Small hairlines, traces of usage and minor losses around the foot rim. Two areas of old repair to shallow surface chips (ca. 3 x 3 cm each).

Weight: 16.4 kg (excl. cover) and 1,576 g (the cover)

Dimensions: Height 50.4 cm

The present caddy was used to store ‘Dian’ tea, served only in a sacred hall where all the monks of a monastery or temple would gather before the Buddha, after the tea bell was struck by the tea monk as an initiation of the tea ceremony.

The visvavajra on the cover is a most potent and indestructible symbol of protection, placed in this particular spot not only to dispel evil, temptation, and deception from the four directions, but also to repudiate individuals from withdrawing - thus desecrating - the precious contents of this caddy.

The double vajra motif appears to have entered the Chinese repertoire of porcelain designs with the increased popularity of Lamaism – Tibetan Buddhism - in the Yuan dynasty. As early as 1207 Ghengis Khan sent envoys to Tibet, and a system developed so that Tibet accepted Mongol protection and suzerainty while providing the Mongols with spiritual guidance. In 1239, however, a Mongol army under Koden, second son of Ogodai Khan attacked Tibet, and the Tibetans decided to negotiate. The result was that Tibet submitted to the Mongols and the latter appointed the abbot of the Sakya monastery to exercise political authority over the whole of Tibet. The magic of Tantric Buddhism appealed to the Mongols and when they were initiated into the practices of Lamaism, they began to adopt that type of Buddhism to take the place of their own Shamanism.

When Kublai Khan took over the great Khanate in 1260, he made Lamaism the national religion of the Mongols. After the Mongols established the Yuan dynasty in China in 1279, Lamaism flourished, receiving huge grants of land from the ruling house and the nobility. Tibetan Buddhist iconography appeared on objects in a variety of media made for the Yuan court. These included motifs such as the double vajra, which is seen on blue and white porcelain of the period. The influence of Lamaism on these porcelains came not only from the interests of the Mongols themselves, but from the Tibetan and Nepalese craftsmen who held high positions at the imperial porcelain kiln at Jingdezhen. The famous Nepalese artist Aniko (1245-1306) was appointed head of the Imperial workshops in 1278.

In the Ming dynasty a number of the Chinese emperors had a genuine interest in Lamaist Buddhism, but they also patronized Lamaism as a way of maintaining control over both the Tibetans and the Mongols, through the support of the powerful high lamas. The Yongle Emperor involved both Tibetan and Nepalese craftsmen in the building of his new palace in Beijing. He also involved them in the running of the Imperial workshops, as had the previous Mongol dynasty. Their influence can clearly be seen in the works such as exquisite gilt-bronze Buddhist figures in Tibetan-Chinese style made during this reign. These pieces and those of the succeeding Xuande period (1426-35) were made with reign marks and for ritual use by the Imperial household or as gifts from the emperor to high Tibetan lamas favored by the Chinese court.

During the reign of the Chenghua Emperor (1465-87) there were 437 Tibetan monks holding high rank and 789 lamas who could enter the court freely. The emperor’s advisers became concerned by this preoccupation with Buddhism and the amount spent by the emperor in connection with it, so that they suggested a sharp reduction in his support of Buddhism. This appears to have been adopted for the middle part of his reign, but his resumption of expressed interest in Buddhism can clearly be observed through the arts produced in the latter years of the Chenghua reign. Among these, the ceramics made at the imperial kiln provide a good indication of the incorporation of Buddhist motifs, including Tibetan Buddhist motifs, on porcelains made for the court.

Literature comparison: A somewhat simpler double-vajra and ribbon design can be seen on the interior of a blue and white dish, in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing, illustrated in Blue and White Porcelain with Underglaze Red (II), The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum, vol. 35, Hong Kong, 2000, p. 9, no. 7. A dish with double vajra on the interior, which is similar to the Beijing dish, was excavated at the Ming imperial kilns from the late Chenghua stratum and is illustrated in The Emperor’s broken china – Reconstructing Chenghua porcelain, London, 1995, p. 77, no. 102. A double vajra can also be seen in the central medallion on the interior of a large blue and white bowl in the collection of the Idemitsu Museum, illustrated in Chinese Ceramics in the Idemitsu Collection, Tokyo, 1987, color plate 140. Compare also to a dish with a double vajra from the collection of Sir John Addis, illustrated by Jessica Harrison-Hall in Ming Ceramics in the British Museum, London, 2001, no. 6:10.

Auction result comparison: Compare with a blue and white dish from the Ming dynasty, showing a closely related double vajra as on the present caddy, at Christie’s London in Rarity and Refinement: Treasures from a Distinguished East Asian Collection, on 15 May 2018, lot 7, sold for GBP 81,250.

明代末期大型青花金剛杵茶葉罐

中國,十五世紀末至十七世紀中葉。茶葉罐外壁可見太獅少獅戲珠圖,四周是滾動的雲彩和火焰,頂部纏枝蓮紋,側面可見金剛杵。

來源:英國私人收藏.

品相:總體而言狀況良好,有磨損,燒傷缺陷,窯渣,麻點和燒結現象,露胎部部成橙色,完全符合明代晚期瓷器的特徵。 細小的裂縫,使用痕跡和腳沿周圍的輕微磕損。有兩處舊時修復區域小開片(每片約3 x 3厘米)。

重量:不含蓋16.4 公斤;蓋1,576 克

尺寸:高50.4厘米

拍賣結果比較:於2018年5月15日 倫敦佳士得 Rarity and Refinement: Treasures from a Distinguished East Asian Collection 拍場中,與一件明代時期藍白盤比較,出与本罐密切相关的双金刚,lot 7,售價GBP 81,250。

Zacke Live Online Bidding

Our online bidding platform makes it easier than ever to bid in our auctions! When you bid through our website, you can take advantage of our premium buyer's terms without incurring any additional online bidding surcharges.

To bid live online, you'll need to create an online account. Once your account is created and your identity is verified, you can register to bid in an auction up to 12 hours before the auction begins.

Intended Spend and Bid Limits

When you register to bid in an online auction, you will need to share your intended maximum spending budget for the auction. We will then review your intended spend and set a bid limit for you. Once you have pre-registered for a live online auction, you can see your intended spend and bid limit by going to 'Account Settings' and clicking on 'Live Bidding Registrations'.

Your bid limit will be the maximum amount you can bid during the auction. Your bid limit is for the hammer price and is not affected by the buyer’s premium and VAT. For example, if you have a bid limit of €1,000 and place two winning bids for €300 and €200, then you will only be able to bid €500 for the rest of the auction. If you try to place a bid that is higher than €500, you will not be able to do so.

Online Absentee and Telephone Bids

You can now leave absentee and telephone bids on our website!

Absentee Bidding

Once you've created an account and your identity is verified, you can leave your absentee bid directly on the lot page. We will contact you when your bids have been confirmed.

Telephone Bidding

Once you've created an account and your identity is verified, you can leave telephone bids online. We will contact you when your bids have been confirmed.

Classic Absentee and Telephone Bidding Form

You can still submit absentee and telephone bids by email or fax if you prefer. Simply fill out the Absentee Bidding/Telephone bidding form and return it to us by email at office@zacke.at or by fax at +43 (1) 532 04 52 20. You can download the PDF from our Upcoming Auctions page.

How-To Guides

How to Create Your Personal Zacke Account

How to Register to Bid on Zacke Live

How to Leave Absentee Bids Online

How to Leave Telephone Bids Online

中文版本的操作指南

创建新账号

注册Zacke Live在线直播竞拍(免平台费)

缺席投标和电话投标

Third-Party Bidding

We partner with best-in-class third-party partners to make it easy for you to bid online in the channel of your choice. Please note that if you bid with one of our third-party online partners, then there will be a live bidding surcharge on top of your final purchase price. You can find all of our fees here. Here's a full list of our third-party partners:

- 51 Bid Live

- EpaiLive

- ArtFoxLive

- Invaluable

- LiveAuctioneers

- the-saleroom

- lot-tissimo

- Drouot

Please note that we place different auctions on different platforms. For example, in general, we only place Chinese art auctions on 51 Bid Live.

Bidding in Person

You must register to bid in person and will be assigned a paddle at the auction. Please contact us at office@zacke.at or +43 (1) 532 04 52 for the latest local health and safety guidelines.