5th Mar, 2021 10:00

TWO-DAY AUCTION - Fine Chinese Art / 中國藝術集珍 / Buddhism & Hinduism

9

AN EXCEPTIONAL AND VERY LARGE CANTON ENAMEL ‘SCHOLARS’ DISH, EARLY 18TH CENTURY

十八世紀初廣州銅胎畫琺琅開光文人賞畫圓盤

Sold for €10,112

including Buyer's Premium

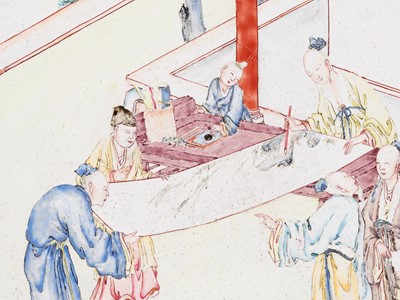

China. This piece is notable for its imposing size, the broad surface of which has been delicately rendered with a rich scene of scholars, literati and pupils observing an artist working on a scroll, painted with bamboo springing from craggy rockwork, the yet unfinished oeuvre being the talk of the gathering.

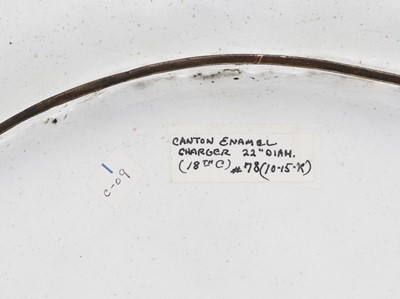

Provenance: From a private estate in Pennsylvania, USA. The backside with an old collector’s label inscribed “C-09” and a second label with the inscription “Canton Enamel Charger 22” Diam. (18TH C) #78 (10.15.K)”.

Condition: The foot rim with a hole drilled for suspension. The center with circular hairlines along the foot and two old fillings, each the size of a coin. The outer border with an old, restored section of ca. 10-15 cm, barely extending into the yellow border, mirrored at the back. Minuscule firing flaws, pitting, hairlines, dents, losses and fills. The metal mounts with a fine, naturally grown patina. Old wear and traces of use. Overall, in good condition, especially considering the magnificent size of 2.365 cm², with less than 60 cm² of restored area, equivalent to only 2.5% (!) of the total surface.

Weight: 3.7 kg

Dimensions: 55 cm

Furthermore, we find a building with a terrace, a garden with scholar’s rocks, an imposing Ming dynasty altar table with a bitong and various brushes, an inkstone and several garden stools, as well as a peaceful lake and mountains in the far distance completing the inspiring scene.

The cavetto with a dense scroll of pink peonies and lavender-colored lotus against an Imperial yellow ground, all within two circumferential bands of leaves and vines. The reverse shows a neatly painted still life of two peaches, lingzhi, flowers and a single bat against a white ground. The border with a band of grapes.

The present dish is among the earliest examples of the successful combination of Western imaging techniques with traditional Chinese motifs during the first half of the 18th century. The subtle gradations of tone and the rendering of light and shade are particularly successful in the central panel, where cautious shading is introduced along the walls and canopy of the building. Even these few shades already give the composition a certain three-dimensional depth, heretofore unknown in Chinese painting. Moreover, the similarly rendered pink flowers are depicted in full bloom and appear to loom out from the contrasting yellow background. The fusion of East and West is therefore not only found on a technical level, but also in the stylistic approach to this painting, where the Chinese tradition of outlining has cleverly been combined with the European pursuit of naturalism through shading. Wares that combine a finely enameled scholarly motif on the interior with a vibrant yellow ground exterior were also produced in porcelain and celebrate the newly developed Famille Rose palette of the early eighteenth century. Tang Ying (1682–1756), as of 1728 the superintendent of the Imperial Kilns at Jingdezhen, notes in his work “A Brief Account of Ceramics”, that yangcai (Western color) enamel wares should be classified as combining falang glazes with Western painting styles (see the National Palace Museum exhibition catalog, Stunning Decorative Porcelains from the Qianlong Reign, Taipei, 2008, pp. 32-40).

Painting in enamels on copper is essentially a Western art that gained prominence in northern Europe during the Renaissance and flourished in China under the reign of the Qianlong emperor. Once the piece was shaped, the copper was prepared with a ground of plain enamel to receive the painting in glassy pigments which then bonded to it by firing. The resulting clear and brilliant contrast of colors, which allowed for ornate decoration, was particularly suited to the young Qianlong emperor's taste for the opulent and exotic. The technique was first introduced to Guangzhou by Jesuit missionaries who entered the port with samples of Limoges wares from Europe around 1700. It was then presented to the Palace Workshop between 1714 and 1716 by the enamel factories in Guangzhou, who supplied versatile artisans dedicated to developing and improving the standard of the imperial Enamel Workshop (see Yang Boda in the catalog to the exhibition Tributes from Guangzhou to the Qing Court, Art Gallery, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, 1987, page 63).

Curator’s Summary: The frugal use of shading points to an early date during the first period of enamel production, which can possibly be even narrowed to 1710-1725. After this period, shading became more sophisticated and stippling was introduced. It is even possible that this monumental work, obviously conceived to impress, and difficult to make with the limited production capacities of the time, was among the few large template pieces presented to the Imperial Palace Workshop between 1714 and 1716 by the enamel factories in Guangzhou. This would explain the lasting albeit simplified reappearance of closely related scholarly motifs in later imperial works. Overall, the present dish must therefore not only be regarded as extremely rare, but also as an important contributor to what was later to become the most sophisticated producer of enamel wares in the history of mankind: The Imperial Palace Workshops in Beijing.

Literature comparison: A similar use of yellow ground with multi-colored floral scrolls along panels containing depictions of scholars in garden landscapes can be seen on a Qianlong hand-warmer – with a red enamel six-character Qianlong seal mark within a single square – in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei (illustrated in Enamel Ware in the Ming and Qing Dynasties, p. 243, no. 134) although the frames of the panels on the hand-warmer are in red tones and created using more sophisticated abutted S- and C-shaped elements. The use of imperial yellow grounds ornamented with multi-colored floral scrolls was much admired by the court in the Qianlong reign and can be seen on a number of items in a range of forms preserved in the collections of the Palace Museum, Beijing, and the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

A scene of scholars in a garden setting, related to the one on the present plate, appears on a Qianlong enameled tea container in the collection of the State Museum of Oriental Art, Moscow (illustrated by Marina Neglinskaya in Kitayske raspisnie zmali, Moscow, 1995, cat. 38), although in the case of the Moscow piece, one scholar is playing the qin while another listens, and a servant approaches with refreshments. The enamels on the Moscow tea container are less rich than those on the present plate and the hand-warmer from the National Palace Museum Collection, and the dominant color in the background is blue rather than yellow, but it is interesting to note that the style was appreciated by the European elite as well as those in China.

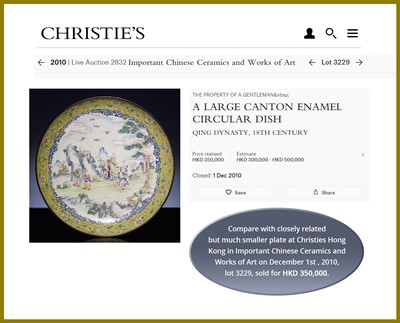

Auction result comparison: Compare with a closely related but much smaller plate at Christie's Hong Kong in Important Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art on December 1st 2010, lot 3229, sold for HKD 350,000.

十八世紀初廣州銅胎畫琺琅開光文人賞畫圓盤

中國. 這件圓盤尺寸宏偉,盤内開光,繪畫精美,文人及其學生欣賞一位畫家在捲軸上作畫的場景,四周山水湖泊以及院内假山竹林。

來源: 美國賓夕法尼亞州私人遺產。盤底有老藏家的標簽 “C-09” 以及第二個標簽 “Canton Enamel Charger 22” Diam. (18TH C) #78 (10.15.K)”。

品相:圈足上鑽有一個用於懸掛的小孔。圈足上有一道圓形細縫,兩個硬幣大小的舊時修補。 外圈纏枝紋帶上有一道大約10-15厘米長的就是修補,幾乎延伸到黃色邊框中,反映在背面。輕微的燒製缺陷,麻點,髮絲線裂紋,凹痕,缺損和修補填充。金屬部位具有自然生長的包漿。舊磨損和使用痕跡。 總體而言,狀況良好,尤其是考慮到2.365平方厘米的宏偉尺寸,恢復面積不到60平方厘米,僅佔整個表面的2.5%(!)。

重量:3.7公斤

尺寸:55 厘米

畫面中細節精緻,從庭院、花園到假山以及明代風格的案桌,桌上的筆筒、筆墨等,遠處的湖泊。

盤沿上黃地琺琅彩繪畫纏枝蓮紋與牡丹,色彩濃鬱。圓盤背面可見兩個桃子、靈芝、花朵和一隻蝙蝠。

此盤是18世紀上半葉西方影像技術與中國傳統繪畫成功結合的最早例子之一。盤中央繪畫中體現了色調的細微漸變以及明暗渲染的成功,并且謹慎的在建築物如牆壁和屋頂描繪中引入了陰影技巧。即使這幾個色調已經得到該組合物一定的三維深度,在此時期之前中國繪畫并未使用。東西方技巧的融合不僅可以在技術層面而且可以在這幅畫的風格方法上找到。

在銅胎上使用琺瑯繪畫本身是一種西方藝術,在文藝復興時期廣為人知,並在乾隆皇帝統治下在中國蓬勃發展,清晰鮮明的色彩對比使裝飾華麗,特別適合年輕的乾隆皇帝對華麗且富有異國情調的品味。這項技術首先由耶穌會傳教士於1700年左右傳入廣州,然後在1714至1716年間,從廣州進入北京御用工坊,他們提供了致力於發展的工匠。並提高了琺瑯工場的標準(見楊伯達,香港博覽館展覽目錄,《從廣州到清宮的貢品》,香港中文大學,香港,1987年,第63頁)。

策展人摘要:在琺琅彩繪中簡潔使用陰影的技巧幾乎可以確定在1710年至1725年。在此之後,陰影使用變得更加複雜。這個圓盤可能是廣州琺瑯工坊在1714至1716年間向御用工坊展示的少數大型模板作品之一。這個圓盤不僅稀有,而且還將是人類歷史上琺琅彩繪畫技術的重要貢獻者。

文獻比較:一件同樣使用了黃色琺琅釉地纏枝紋以及園中文人情景的琺琅釉器皿可參見臺北故宮博物院乾隆暖手爐 (illustrated in Enamel Ware in the Ming and Qing Dynasties, p. 243, no. 134) ;與圓盤上文人場景相似的場景可見於收藏于莫斯科東亞美術館的乾隆時期茶具 (illustrated by Marina Neglinskaya in Kitayske raspisnie zmali, Moscow, 1995, cat. 38)。

拍賣結果比較:一件相近但小一些的圓盤售于香港佳士得Important Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art 拍場,2010年12月1日,lot 3229,售價 HKD 350,000.

China. This piece is notable for its imposing size, the broad surface of which has been delicately rendered with a rich scene of scholars, literati and pupils observing an artist working on a scroll, painted with bamboo springing from craggy rockwork, the yet unfinished oeuvre being the talk of the gathering.

Provenance: From a private estate in Pennsylvania, USA. The backside with an old collector’s label inscribed “C-09” and a second label with the inscription “Canton Enamel Charger 22” Diam. (18TH C) #78 (10.15.K)”.

Condition: The foot rim with a hole drilled for suspension. The center with circular hairlines along the foot and two old fillings, each the size of a coin. The outer border with an old, restored section of ca. 10-15 cm, barely extending into the yellow border, mirrored at the back. Minuscule firing flaws, pitting, hairlines, dents, losses and fills. The metal mounts with a fine, naturally grown patina. Old wear and traces of use. Overall, in good condition, especially considering the magnificent size of 2.365 cm², with less than 60 cm² of restored area, equivalent to only 2.5% (!) of the total surface.

Weight: 3.7 kg

Dimensions: 55 cm

Furthermore, we find a building with a terrace, a garden with scholar’s rocks, an imposing Ming dynasty altar table with a bitong and various brushes, an inkstone and several garden stools, as well as a peaceful lake and mountains in the far distance completing the inspiring scene.

The cavetto with a dense scroll of pink peonies and lavender-colored lotus against an Imperial yellow ground, all within two circumferential bands of leaves and vines. The reverse shows a neatly painted still life of two peaches, lingzhi, flowers and a single bat against a white ground. The border with a band of grapes.

The present dish is among the earliest examples of the successful combination of Western imaging techniques with traditional Chinese motifs during the first half of the 18th century. The subtle gradations of tone and the rendering of light and shade are particularly successful in the central panel, where cautious shading is introduced along the walls and canopy of the building. Even these few shades already give the composition a certain three-dimensional depth, heretofore unknown in Chinese painting. Moreover, the similarly rendered pink flowers are depicted in full bloom and appear to loom out from the contrasting yellow background. The fusion of East and West is therefore not only found on a technical level, but also in the stylistic approach to this painting, where the Chinese tradition of outlining has cleverly been combined with the European pursuit of naturalism through shading. Wares that combine a finely enameled scholarly motif on the interior with a vibrant yellow ground exterior were also produced in porcelain and celebrate the newly developed Famille Rose palette of the early eighteenth century. Tang Ying (1682–1756), as of 1728 the superintendent of the Imperial Kilns at Jingdezhen, notes in his work “A Brief Account of Ceramics”, that yangcai (Western color) enamel wares should be classified as combining falang glazes with Western painting styles (see the National Palace Museum exhibition catalog, Stunning Decorative Porcelains from the Qianlong Reign, Taipei, 2008, pp. 32-40).

Painting in enamels on copper is essentially a Western art that gained prominence in northern Europe during the Renaissance and flourished in China under the reign of the Qianlong emperor. Once the piece was shaped, the copper was prepared with a ground of plain enamel to receive the painting in glassy pigments which then bonded to it by firing. The resulting clear and brilliant contrast of colors, which allowed for ornate decoration, was particularly suited to the young Qianlong emperor's taste for the opulent and exotic. The technique was first introduced to Guangzhou by Jesuit missionaries who entered the port with samples of Limoges wares from Europe around 1700. It was then presented to the Palace Workshop between 1714 and 1716 by the enamel factories in Guangzhou, who supplied versatile artisans dedicated to developing and improving the standard of the imperial Enamel Workshop (see Yang Boda in the catalog to the exhibition Tributes from Guangzhou to the Qing Court, Art Gallery, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, 1987, page 63).

Curator’s Summary: The frugal use of shading points to an early date during the first period of enamel production, which can possibly be even narrowed to 1710-1725. After this period, shading became more sophisticated and stippling was introduced. It is even possible that this monumental work, obviously conceived to impress, and difficult to make with the limited production capacities of the time, was among the few large template pieces presented to the Imperial Palace Workshop between 1714 and 1716 by the enamel factories in Guangzhou. This would explain the lasting albeit simplified reappearance of closely related scholarly motifs in later imperial works. Overall, the present dish must therefore not only be regarded as extremely rare, but also as an important contributor to what was later to become the most sophisticated producer of enamel wares in the history of mankind: The Imperial Palace Workshops in Beijing.

Literature comparison: A similar use of yellow ground with multi-colored floral scrolls along panels containing depictions of scholars in garden landscapes can be seen on a Qianlong hand-warmer – with a red enamel six-character Qianlong seal mark within a single square – in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei (illustrated in Enamel Ware in the Ming and Qing Dynasties, p. 243, no. 134) although the frames of the panels on the hand-warmer are in red tones and created using more sophisticated abutted S- and C-shaped elements. The use of imperial yellow grounds ornamented with multi-colored floral scrolls was much admired by the court in the Qianlong reign and can be seen on a number of items in a range of forms preserved in the collections of the Palace Museum, Beijing, and the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

A scene of scholars in a garden setting, related to the one on the present plate, appears on a Qianlong enameled tea container in the collection of the State Museum of Oriental Art, Moscow (illustrated by Marina Neglinskaya in Kitayske raspisnie zmali, Moscow, 1995, cat. 38), although in the case of the Moscow piece, one scholar is playing the qin while another listens, and a servant approaches with refreshments. The enamels on the Moscow tea container are less rich than those on the present plate and the hand-warmer from the National Palace Museum Collection, and the dominant color in the background is blue rather than yellow, but it is interesting to note that the style was appreciated by the European elite as well as those in China.

Auction result comparison: Compare with a closely related but much smaller plate at Christie's Hong Kong in Important Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art on December 1st 2010, lot 3229, sold for HKD 350,000.

十八世紀初廣州銅胎畫琺琅開光文人賞畫圓盤

中國. 這件圓盤尺寸宏偉,盤内開光,繪畫精美,文人及其學生欣賞一位畫家在捲軸上作畫的場景,四周山水湖泊以及院内假山竹林。

來源: 美國賓夕法尼亞州私人遺產。盤底有老藏家的標簽 “C-09” 以及第二個標簽 “Canton Enamel Charger 22” Diam. (18TH C) #78 (10.15.K)”。

品相:圈足上鑽有一個用於懸掛的小孔。圈足上有一道圓形細縫,兩個硬幣大小的舊時修補。 外圈纏枝紋帶上有一道大約10-15厘米長的就是修補,幾乎延伸到黃色邊框中,反映在背面。輕微的燒製缺陷,麻點,髮絲線裂紋,凹痕,缺損和修補填充。金屬部位具有自然生長的包漿。舊磨損和使用痕跡。 總體而言,狀況良好,尤其是考慮到2.365平方厘米的宏偉尺寸,恢復面積不到60平方厘米,僅佔整個表面的2.5%(!)。

重量:3.7公斤

尺寸:55 厘米

畫面中細節精緻,從庭院、花園到假山以及明代風格的案桌,桌上的筆筒、筆墨等,遠處的湖泊。

盤沿上黃地琺琅彩繪畫纏枝蓮紋與牡丹,色彩濃鬱。圓盤背面可見兩個桃子、靈芝、花朵和一隻蝙蝠。

此盤是18世紀上半葉西方影像技術與中國傳統繪畫成功結合的最早例子之一。盤中央繪畫中體現了色調的細微漸變以及明暗渲染的成功,并且謹慎的在建築物如牆壁和屋頂描繪中引入了陰影技巧。即使這幾個色調已經得到該組合物一定的三維深度,在此時期之前中國繪畫并未使用。東西方技巧的融合不僅可以在技術層面而且可以在這幅畫的風格方法上找到。

在銅胎上使用琺瑯繪畫本身是一種西方藝術,在文藝復興時期廣為人知,並在乾隆皇帝統治下在中國蓬勃發展,清晰鮮明的色彩對比使裝飾華麗,特別適合年輕的乾隆皇帝對華麗且富有異國情調的品味。這項技術首先由耶穌會傳教士於1700年左右傳入廣州,然後在1714至1716年間,從廣州進入北京御用工坊,他們提供了致力於發展的工匠。並提高了琺瑯工場的標準(見楊伯達,香港博覽館展覽目錄,《從廣州到清宮的貢品》,香港中文大學,香港,1987年,第63頁)。

策展人摘要:在琺琅彩繪中簡潔使用陰影的技巧幾乎可以確定在1710年至1725年。在此之後,陰影使用變得更加複雜。這個圓盤可能是廣州琺瑯工坊在1714至1716年間向御用工坊展示的少數大型模板作品之一。這個圓盤不僅稀有,而且還將是人類歷史上琺琅彩繪畫技術的重要貢獻者。

文獻比較:一件同樣使用了黃色琺琅釉地纏枝紋以及園中文人情景的琺琅釉器皿可參見臺北故宮博物院乾隆暖手爐 (illustrated in Enamel Ware in the Ming and Qing Dynasties, p. 243, no. 134) ;與圓盤上文人場景相似的場景可見於收藏于莫斯科東亞美術館的乾隆時期茶具 (illustrated by Marina Neglinskaya in Kitayske raspisnie zmali, Moscow, 1995, cat. 38)。

拍賣結果比較:一件相近但小一些的圓盤售于香港佳士得Important Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art 拍場,2010年12月1日,lot 3229,售價 HKD 350,000.

Zacke Live Online Bidding

Our online bidding platform makes it easier than ever to bid in our auctions! When you bid through our website, you can take advantage of our premium buyer's terms without incurring any additional online bidding surcharges.

To bid live online, you'll need to create an online account. Once your account is created and your identity is verified, you can register to bid in an auction up to 12 hours before the auction begins.

Intended Spend and Bid Limits

When you register to bid in an online auction, you will need to share your intended maximum spending budget for the auction. We will then review your intended spend and set a bid limit for you. Once you have pre-registered for a live online auction, you can see your intended spend and bid limit by going to 'Account Settings' and clicking on 'Live Bidding Registrations'.

Your bid limit will be the maximum amount you can bid during the auction. Your bid limit is for the hammer price and is not affected by the buyer’s premium and VAT. For example, if you have a bid limit of €1,000 and place two winning bids for €300 and €200, then you will only be able to bid €500 for the rest of the auction. If you try to place a bid that is higher than €500, you will not be able to do so.

Online Absentee and Telephone Bids

You can now leave absentee and telephone bids on our website!

Absentee Bidding

Once you've created an account and your identity is verified, you can leave your absentee bid directly on the lot page. We will contact you when your bids have been confirmed.

Telephone Bidding

Once you've created an account and your identity is verified, you can leave telephone bids online. We will contact you when your bids have been confirmed.

Classic Absentee and Telephone Bidding Form

You can still submit absentee and telephone bids by email or fax if you prefer. Simply fill out the Absentee Bidding/Telephone bidding form and return it to us by email at office@zacke.at or by fax at +43 (1) 532 04 52 20. You can download the PDF from our Upcoming Auctions page.

How-To Guides

How to Create Your Personal Zacke Account

How to Register to Bid on Zacke Live

How to Leave Absentee Bids Online

How to Leave Telephone Bids Online

中文版本的操作指南

创建新账号

注册Zacke Live在线直播竞拍(免平台费)

缺席投标和电话投标

Third-Party Bidding

We partner with best-in-class third-party partners to make it easy for you to bid online in the channel of your choice. Please note that if you bid with one of our third-party online partners, then there will be a live bidding surcharge on top of your final purchase price. You can find all of our fees here. Here's a full list of our third-party partners:

- 51 Bid Live

- EpaiLive

- ArtFoxLive

- Invaluable

- LiveAuctioneers

- the-saleroom

- lot-tissimo

- Drouot

Please note that we place different auctions on different platforms. For example, in general, we only place Chinese art auctions on 51 Bid Live.

Bidding in Person

You must register to bid in person and will be assigned a paddle at the auction. Please contact us at office@zacke.at or +43 (1) 532 04 52 for the latest local health and safety guidelines.